The Wall Street Journal: China’s Breakneck Development Brings Flooding in Its Wake

BEIJING—It seemed the water from dozens of filled-in lakes was returning to submerge the central Chinese megacity of Wuhan this month.

The lakes had been sacrificed during China’s pell-mell urbanization, and now, in a parable of poor development, cars and homes were being swallowed by flooding after torrential rains. A stadium turned into a virtual bathtub. Online, people circulated photos of the high-speed rail station—a potent symbol of China’s modernization—partly submerged. The city of 10.6 million people came to a near standstill for days, power and public transportation cut off.

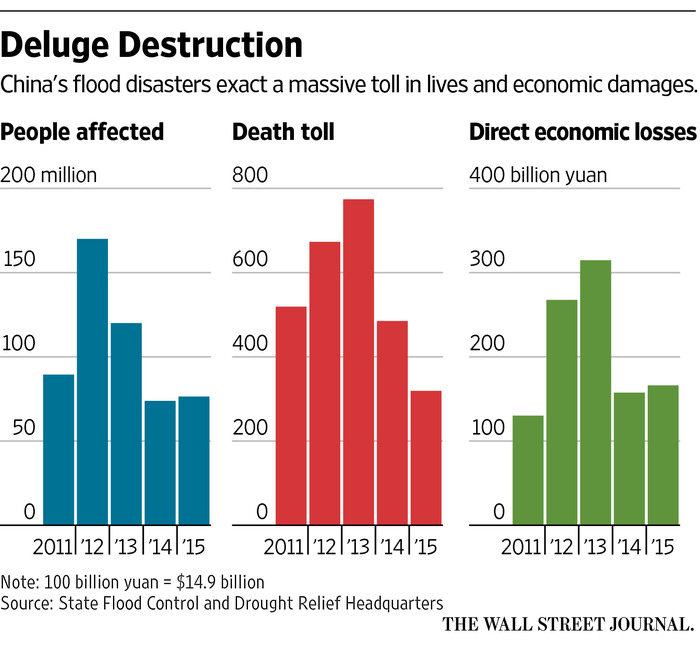

Across central and southern China this year, flooding has affected more than 60 million people, with more than 200 killed and 147 billion yuan ($22 billion) in losses.

The country has long suffered from deadly floods, which the government has sought to control through extensive dam-building. As China has urbanized, flooding has become a regular feature of its cities, notably in the more developed south and east. Between 2011 and 2015, direct economic losses came to 1 trillion yuan, government data shows.

Wuhan, once an area of “one hundred lakes” as well as rainfall-absorbing wetlands, became a city of pavement as high-rises and roads mushroomed across the city, gobbling up about 90 lakes since the 1950s, according to state media.

“When I was a child, lakes, pools and reservoirs were everywhere surrounding my home,” a shopkeeper surnamed Li said. “The reason we have such a serious flooding is 100% related to reclamation.”

In citing reasons for this year’s particularly bad flooding, Wuhan officials included the city’s low altitude and the El Niño weather phenomenon, which causes unusually dry weather in some parts of the world and wet weather in others. But at a recent news conference a local water-authority official said the city had “overly emphasized” economic development and set too-low standards for its infrastructure. Wuhan’s water authority didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Wuhan’s pattern is a familiar one.

An improvised pontoon bridge helping keep a pedestrian’s feet dry in Wuhan this month.

PHOTO: WANG HE/GETTY IMAGES

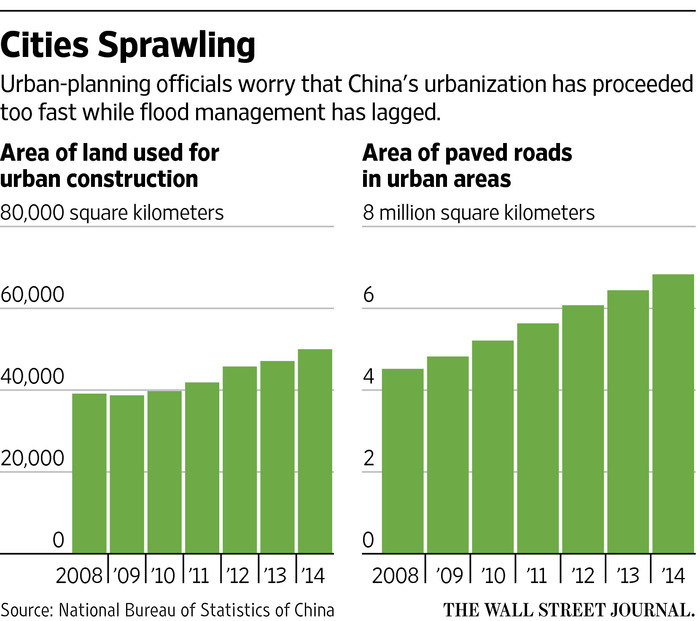

“China’s urban construction was carried out at too fast a pace,” says JiaHaifeng, associate professor with Tsinghua University’s environmental science and engineering department. Officials have tended to focus on visible projects such as roads, bridges and housing, he said. “They emphasized infrastructure above ground, but not so much infrastructure below ground.”

Many roads are built without being properly leveled, said Andrew Buck, an urban planner at Beijing landscape-architecture firm Turenscape, meaning that water easily accumulates. Older drainage systems often can’t accommodate current demands.

Between 2008 and 2010, the latest available official statistics, 62% of Chinese cities surveyed experienced flooding. The capital is no exception: In 2012, 79 people died after flooding in Beijing.

Environmentalists say they are encouraged by the government’s recent “sponge city” pilot programs introducing infrastructure such as permeable pavement and adding rainwater-collection facilities across the country. The Chinese government said last year that it hopes to have modern sewer systems and rainwater-absorbing infrastructure in 20% of cities by 2020 and 80% by 2030.

This is taking China’s long tradition of reshaping the landscape in a new direction. During Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward, millions of workers were mobilized for reclamation projects to create more state farms, including in Wuhan’s province of Hubei. According to government figures, the province has lost about half of its more than 1,000 lakes since the 1950s.

One big reason for the disappearance of wetlands and lakes, says Yu Kongjian, dean of Peking University’s College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, is that it is easier to get approval to develop bare public areas than farmland.

”The government can make a lot of profit by selling this cheap land,” says Mr. Yu. Land sales have long served as a crucial source of income for local governments. As a consequence, China’s urban sprawl has metastasized so quickly that more than 60% of cities of over 100,000 people have actually grown less crowded even as their populations have soared, according to a World Bank analysis.

The monsoon climate means that in parts of China the vast majority of the rain falls in June, July and August, Mr. Yu says. That makes it poorly suited to the current flood-control model of pipes and drainage systems, borrowed from the Soviet Union. Given the country’s propensity for both bad droughts and floods, experts say, what’s needed is better rainwater collection and use.

“We are fighting against the water, but water is not an enemy,” says Mr. Yu. “The issue is poor urban planning.”

—Kersten Zhang contributed to this article.